|

| Rio Marañon in Chachapoyas photo - Omar Carbajal ©PromPeru |

After their extended stay in the Casma valley, the

Marañon expedition headed north up the Pacific coast continuing past Trujillo towards Pacasmayo. On the way they investigated ruins in the Nepeña,

Santa, Moche and Jequetepeque valleys. Then they turned inland.

By the beginning of October they were in Cajamarca. From

here on they were in the

highlands, where in Yanakancha, Tello and Hernan stopped to investigate an

obelisk in the courtyard of the Yanakancha hacienda.

The monolith depicted a human

and feline figure on opposing sides, and I have always been keen to discover its

location because of a family photo that we have with Hernan proudly standing

beside it. Well at least now I know where it was. But, intriguingly, whilst

researching for this post I also discovered that no one seems to know where it

is now.

Striking

further east the team finally reached Cochabamba. By now they were penetrating

the densely forested sub-tropical highlands of the Amazonian Andes. This is the

land of the Chachapoyas – the cloud people.

Inca legend talks of the cloud people as being a tall warrior

race, fair of skin and hair. Nowadays the great Chachapoyas fortress of

Kuelap draws tourists to this remote north eastern region of Peru. Rivalling

Machu Pichhu and Sacsayhuaman, the large compound clings to a rocky slope 3,000

metres above sea level, its huge defensive walls more than 20 metres high.

I get the idea from this story that Hernan was not too keen on the tropics.

I get the idea from this story that Hernan was not too keen on the tropics.

The law of the jungle

In which Hernan and Tello are assigned a curious task by a diminuitive figure in a pink hat

There's nowhere more quite like purgatory than the boondocks in November. In the whole of the two weeks that we were in Cochabamba (Chachapoyas) we never saw the sun once, and our shoes and feet were never dry. For those of us who were members of the Archaeological Expedition to the Marañon River, our memories of Cochabamba will forever be the forest, the rain, the fog, the fireflies and the singing of the birds sitting shriveled and soaking wet in the trees.

Amongst the crude huts made out of stakes in the forest clearings, there were also magnificent trapezoid double framed doorways and cisterns made of mounted polished blocks of stone in the pure Inca style. Another feature of this extraordinary jungle landscape, never to be forgotten whether we like it or not, was the little man in the pink cowboy hat. But he will make his entrance a little later in the story.

We had never been in a place where the people worked so little. They seemed to barely work at all. Those that did, lived not in the wooden stake huts, but in simple four walled dwellings, but there were only a couple of them.

One

of these belonged to Venancio Molina, in whose home we were staying. The only thing to eat day after day was

pumpkin soup, and we were lucky to find someone who gave us a few potatoes to supplement

our miserable breakfast of unsweetened mint tea. The man had left the jungle as

a youngster to do his military service. Whilst he was away, he had learnt

something of farming, but on his return had done nothing more than make a few

little holes in the ground and drop in a couple of potatoes or grains of corn.

Happily, here in the lush vegetation of the jungle, Mother Nature had taken

care of the rest.

The

people did raise some cattle, but they were pretty much left to the grace of

God and ran wild as soon as they got the opportunity. They would, when necessary, somehow remember

their erstwhile owners and would come back out of the forest followed by a new

born calf, roaring in desperation with their udders bursting with milk. Once

milked, they would disappear back into the jungle. Mules could be found

wandering around aimlessly in the same fashion.

|

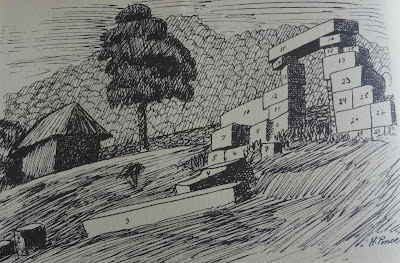

| fig. 2 |

Venancio

Molina served for what could be described as the local gentry. He was a carpenter with his own house and

workshop. He also played the harp and people would come from far and wide to

request his services. His house was the only one in the district that was made

of brick and the only one that had a tiled roof. All the others had straw

roofs.

| photo - Walter Hupiu/Alvaro Rocha rumbosdelperu.com |

Tello was undertaking

an extensive study of the Cochabamba region

and talked to whoever we could find on our small excursions around the area -

although there were, in fact, very few people around. One day, when he was

dictating his notes to me, I ran out of ink and had to climb back up the gully

to the house where we were staying. When I got there, I was greeted by the news

that the police were looking for a dangerous fugitive, although with

characteristic local apathy it appeared that they had limited their pursuit to

having a brief chat with Venancio Molina, who was

also the district’s Governing Lieutenant.

I didn’t

give the matter much more thought, and returned back down the gully where Tello

was waiting for me. There I found him talking to a diminutive stranger.

The man was

quite young, and couldn’t have been much more than one metre tall, dark skinned

with ugly features. The most striking aspect of his appearance was the pink

cowboy hat he wore. Or rather the hat was so large that it might be more

correct to say that the hat wore him! I arrived just

in time to hear him saying to Tello: “Hereabouts those who’s got

the law books, those are the ones who earn the good money. Pué don’t want ‘em

for that. All I want is to defend myself from all those scoundrels.”

| photo - Walter Hupiu/Alvaro Rocha rumbosdelperu.com |

The strange little man shot me an intense

look as I approached and asked if the police had left yet. When I answered in

the affirmative he turned back to Tello.

“See, those townies, they come for me. I saw ‘em over there, Pué didn’t see me … ho no. I could blow those to heaven right now if I wanted. Pff, … what’s the use; theys scared enough o’ me now; theys never going take me to prison. All theys wants is to send the paper to say they come here an’ not found no one”.

Well that much was true. From what I had seen, the guards seemed reluctant to do more than make their report. Access into the gully where we were was by a rough track, barely more than eighty centimeters wide in most places, between rock and abyss or dense forest. It required a certain recklessness to send only one pair of officers into such a place. All the more so considering the nature of the diminutive character in the cowboy hat they had been sent to catch.

“But are you sure it’s you who they’re looking for?” asked Tello.

“Oh yes sir; theys always botherin’ me. That’s why I can’t go to Chachapoya.”

“But you must look for some one to mount your defence. How long can you keep this up? The way things are now, you’ll find yourself never being able to leave this place”.

“Pué, cost me too much. That’s what I want them law books fer. Defend myself with ‘em, hand on book. Don’t know who it was who give ‘em to those who’s put against me … them who’s sayin’ about the stealin’ their beasts”.

He paused and shifted on his feet. “Even say I did kill a man.”

Tello looked him squarely in the eye.

“Then for your own good and your own peace of mind, you must go to them and let them see you are an honest man.”

“Yes pué', doctor; but can’t, can I? ‘S no use, unless I can get them books.” He ran his hand over his chin. “Pué I’m thinkin you can help me here, maybe send me a couple of ‘em books. I’ll pay you fifty soles, fifty soles for the pair.”

“Well I don’t believe that they cost that much,” the archaeologist replied, “but, don’t worry I am going to send you what you want. Let’s see … Hernán, take note here … what’s your name?”

“Eustaquio Bellido.”

“Take note that Eustaquio Bellido of Cochabamba, needs a pair of law books, one civil code and one criminal code.”

"Aha! Those’ll do it.” The little man rubbed his hands together, “one of ‘em for the civil, one of ‘em for the criminal.”

“Maybe you need one also for water rights, or another one for mining, or trade, or military law?” Tello asked innocently.

“No, doctor, what do I need all those fer? The pair; those’ll do me fine.”

“As soon as we arrive in Lima Hernán, remind me, that we must send those codes.”

“Send them here, doctor, to Venancio Molina. I’ll give ‘em their bloody laws, all those who’s blame me. I’m off now. See if them police is gone. ”

The little man turned and disappeared, leaving us intrigued and not a little anxious.

“See, those townies, they come for me. I saw ‘em over there, Pué didn’t see me … ho no. I could blow those to heaven right now if I wanted. Pff, … what’s the use; theys scared enough o’ me now; theys never going take me to prison. All theys wants is to send the paper to say they come here an’ not found no one”.

Well that much was true. From what I had seen, the guards seemed reluctant to do more than make their report. Access into the gully where we were was by a rough track, barely more than eighty centimeters wide in most places, between rock and abyss or dense forest. It required a certain recklessness to send only one pair of officers into such a place. All the more so considering the nature of the diminutive character in the cowboy hat they had been sent to catch.

“But are you sure it’s you who they’re looking for?” asked Tello.

“Oh yes sir; theys always botherin’ me. That’s why I can’t go to Chachapoya.”

“But you must look for some one to mount your defence. How long can you keep this up? The way things are now, you’ll find yourself never being able to leave this place”.

“Pué, cost me too much. That’s what I want them law books fer. Defend myself with ‘em, hand on book. Don’t know who it was who give ‘em to those who’s put against me … them who’s sayin’ about the stealin’ their beasts”.

He paused and shifted on his feet. “Even say I did kill a man.”

Tello looked him squarely in the eye.

“Then for your own good and your own peace of mind, you must go to them and let them see you are an honest man.”

“Yes pué', doctor; but can’t, can I? ‘S no use, unless I can get them books.” He ran his hand over his chin. “Pué I’m thinkin you can help me here, maybe send me a couple of ‘em books. I’ll pay you fifty soles, fifty soles for the pair.”

“Well I don’t believe that they cost that much,” the archaeologist replied, “but, don’t worry I am going to send you what you want. Let’s see … Hernán, take note here … what’s your name?”

“Eustaquio Bellido.”

“Take note that Eustaquio Bellido of Cochabamba, needs a pair of law books, one civil code and one criminal code.”

"Aha! Those’ll do it.” The little man rubbed his hands together, “one of ‘em for the civil, one of ‘em for the criminal.”

“Maybe you need one also for water rights, or another one for mining, or trade, or military law?” Tello asked innocently.

“No, doctor, what do I need all those fer? The pair; those’ll do me fine.”

“As soon as we arrive in Lima Hernán, remind me, that we must send those codes.”

“Send them here, doctor, to Venancio Molina. I’ll give ‘em their bloody laws, all those who’s blame me. I’m off now. See if them police is gone. ”

The little man turned and disappeared, leaving us intrigued and not a little anxious.

|

| wild flowers growing in Kuelap photo - Luis Gamero ©PromPeru |

In Tello’s opinion, he did seem to be

rather a dangerous individual and we passed the rest of the afternoon unsettled

in the knowledge that, should he decide to return, we were in a most unfavourable

position, being as we were, in a gorge that had only one way out.

That night Venancio Molina sat playing his harp, whilst I sang local folk songs from my home town and taught him the words to some of them.

After a while Tello brought up the subject of the little man we had met earlier and asked him why he was wanted by the police.

“Him? That’s Bellido. He’s a well known bandit around here. He’s already got a record as long as my arm. I could easily clap the irons on him and take him off to Chuquibamba for transport to the jail in Chachapoyas.

“Why don’t you?”

“We can’t be sure that he wouldn’t escape. Sometimes I’m not here, and he’d only come back and wreak havoc on us all.”

“What! … That little tiny man really is a thug”

“Oh yes, doctor, he’s a menace. He’s fast on his feet and can rustle cattle soon as you like. They say that he’s killed people too.”

“Who would believe it, he’s so tiny, and with that little boy’s face.”

“Doctor, when that ‘little boy’ gets a few drinks inside him, it’s a different story. When he gets going he starts to look for a fight with anyone.

It wasn't good news. We were working in a narrow gorge that formed a natural trap and had nothing even vaguely resembling a weapon with us. the bandit in the pink cowboy hat could easily suppose that we were carrying money or valuables with us, and it woudl take nothing for him to ambush us at any point along the narrow track. The terrain was rough, isolated and so dense with jungle that we would simply disappear without a trace.

We continued our work in a heightened state of alert, but contrary to our fears, our stay passed without further incident. The day that we were due to leave, the pink hatted bandit appeared again. This time he turned up at Molina’s house. He had come to remind us of our promise to send him the law books. The owner of the house kept his distance from the little man. It was only when Molino discovered what his deadly adversary was up to that he decided to take advantage of us in the same way and order a pair of statute books for himself too!

Charged with such an important mission, we set out on our return journey feeling a little safer. But we never did feel completely out of danger until later after we had crossed the Marañon River, two days ride away from Cochabamba.

That night Venancio Molina sat playing his harp, whilst I sang local folk songs from my home town and taught him the words to some of them.

After a while Tello brought up the subject of the little man we had met earlier and asked him why he was wanted by the police.

“Him? That’s Bellido. He’s a well known bandit around here. He’s already got a record as long as my arm. I could easily clap the irons on him and take him off to Chuquibamba for transport to the jail in Chachapoyas.

“Why don’t you?”

“We can’t be sure that he wouldn’t escape. Sometimes I’m not here, and he’d only come back and wreak havoc on us all.”

“What! … That little tiny man really is a thug”

“Oh yes, doctor, he’s a menace. He’s fast on his feet and can rustle cattle soon as you like. They say that he’s killed people too.”

“Who would believe it, he’s so tiny, and with that little boy’s face.”

“Doctor, when that ‘little boy’ gets a few drinks inside him, it’s a different story. When he gets going he starts to look for a fight with anyone.

It wasn't good news. We were working in a narrow gorge that formed a natural trap and had nothing even vaguely resembling a weapon with us. the bandit in the pink cowboy hat could easily suppose that we were carrying money or valuables with us, and it woudl take nothing for him to ambush us at any point along the narrow track. The terrain was rough, isolated and so dense with jungle that we would simply disappear without a trace.

We continued our work in a heightened state of alert, but contrary to our fears, our stay passed without further incident. The day that we were due to leave, the pink hatted bandit appeared again. This time he turned up at Molina’s house. He had come to remind us of our promise to send him the law books. The owner of the house kept his distance from the little man. It was only when Molino discovered what his deadly adversary was up to that he decided to take advantage of us in the same way and order a pair of statute books for himself too!

Charged with such an important mission, we set out on our return journey feeling a little safer. But we never did feel completely out of danger until later after we had crossed the Marañon River, two days ride away from Cochabamba.

|

| Kuelap Fortress photo - César Vallejos ©PromPeru |

No comments :

Post a Comment